It’s about a 10 min. read.

We recently published self-funded research exploring the impact of consumer emotions on the emerging autonomous vehicle (AV) industry—the latest in our ongoing analysis of the relationship between emotion and disruptive technology.

As detailed in a previous post, this study revealed many consumers are skeptical of self-driving cars. Further, even the prospect of using this technology generates a negative emotional response.

We’ve measured the emotional activation of hundreds of brands in dozens of industries and have found, by far, the autonomous vehicle category generates the most intense and widespread overall negative emotions—indicating a critical obstacle this industry must overcome.

The first two steps in charting a path forward are:

Better understanding these emotions can help guide the industry’s marketing efforts and actual customer experiences with this technology.

Overcoming the Right Negative Emotions

Unlike most industries we analyze, it’s more critical for the AV industry to deactivate negative emotions than it is to activate specific positive emotions, although doing both are obviously important.

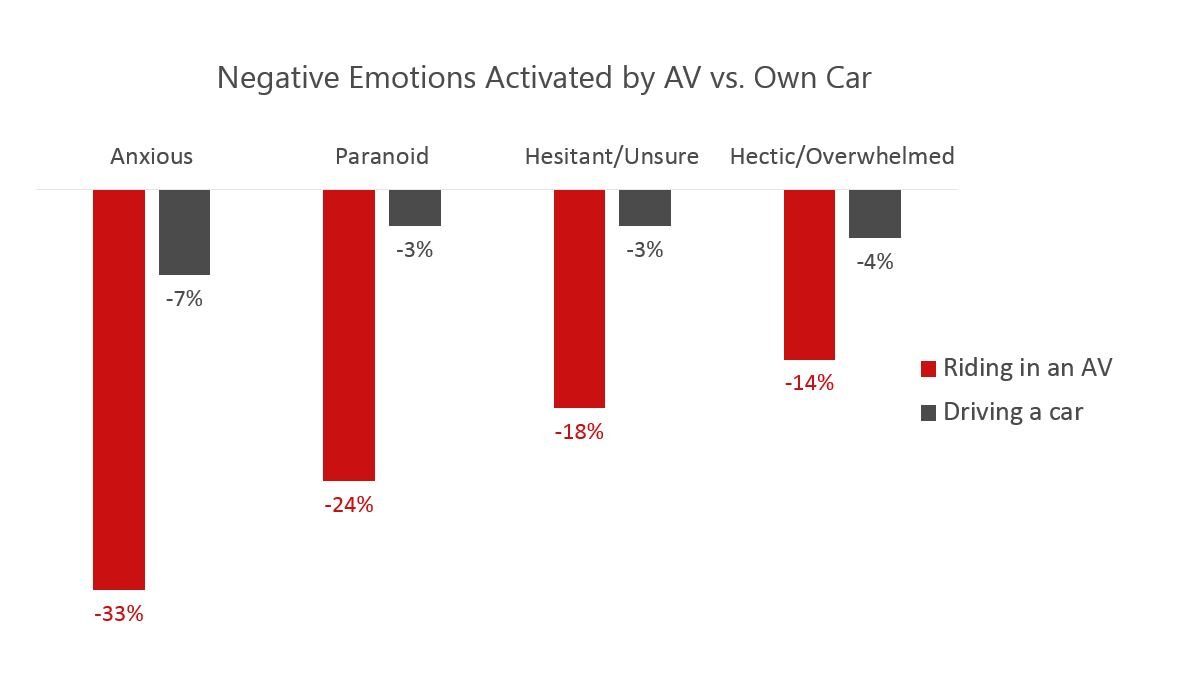

Through our emotional gap analysis, we identified “Anxiety,” “Paranoia,” “Hesitancy,” and feeling “Overwhelmed” as the negative emotions where AVs fare worst when compared to how people feel about driving a car themselves:

Anxiety is no surprise here: people fear the prospect of truly letting AI take over and drive the vehicle with no human intervention.

People are also concerned self-driving car systems could be hacked, which explains the significant feeling of paranoia—an emotion common in a lot of emerging technology we study. Anything “smart” (i.e., connected to the internet) could be hacked, and there are always people who are more concerned about this than others.

Feeling “Hesitant” or “Unsure” also comes up a lot in new and disruptive technology categories. With anything truly new and different, people are unsure of whether it’s ready for primetime, or if they should try it.

The emotions around feeling “Hectic” or “Overwhelmed” are more unique to the AV category. It’s so new and potentially transformative that many people simply can’t process the idea of trusting the technology to get them from point A to point B. It’s overwhelming to really think on the complexity of AV systems, not to mention the myriad road scenarios an AI algorithm will need to be trained well enough to react to.

Positive Emotions Activated by Driving Your Own Car

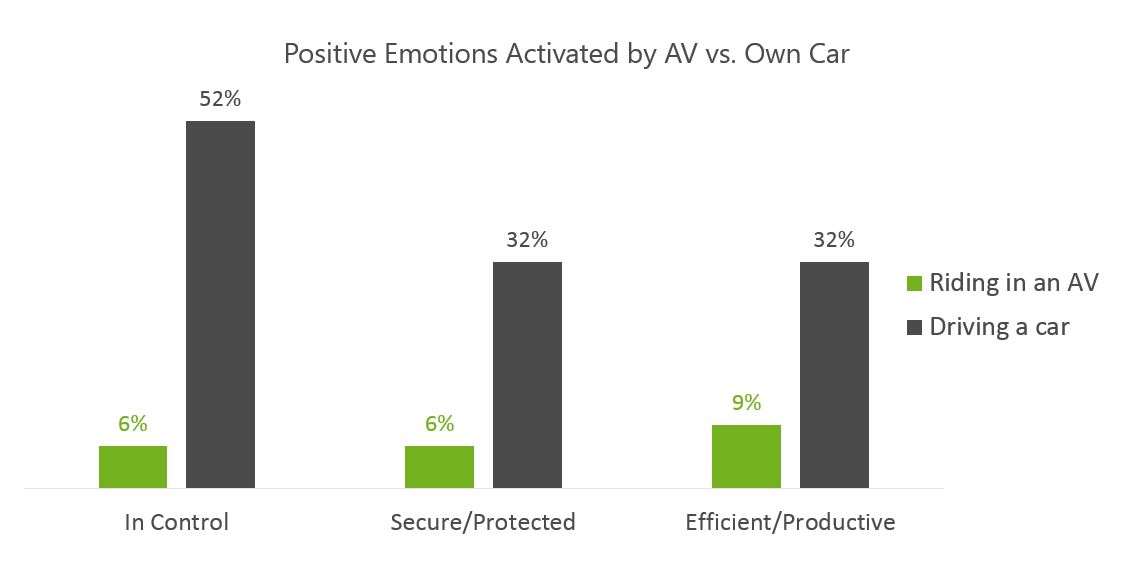

Positive emotions are also important to driving mainstream adoption of a disruptive technology. This is a unique challenge for the AV industry because people already have many positive emotions activated when driving their own car.

Not surprisingly, the biggest positive emotional gap between driving your own car and the prospect of getting in an autonomous vehicle is feeling in control.

The combination of anxiety, paranoia, and losing that feeling of control is a major emotional obstacle to for the autonomous vehicle industry’s path to widespread consumer acceptance. We see this in many AI-driven technology categories where life is increasingly automated and data-driven.

This fear of technology running our lives—and the possibility that it might not always do so benevolently—runs deep and has been prominent in popular culture long before the first self-driven test vehicle ever hit the road.

Source: GIPHY

There’s also a significant gap between feeling “Secure” and “Protected.” As the chart above indicates, people feel a lot more secure and protected when driving their own car, but not so much about self-driving cars. The feeling of insecurity is influencing the high levels of anxiety we see from AVs.

The gap in feeling “Efficient/Productive” is also problematic for the AV industry. In most new technology adoption projects where we run this analysis, that emotion emerges as one of the key determinants of more mainstream consumer adoption. People expect disruptive technologies to make them feel more efficient and productive, but if they don’t truly get that feeling when using the technology, they are unlikely to change their existing habits.

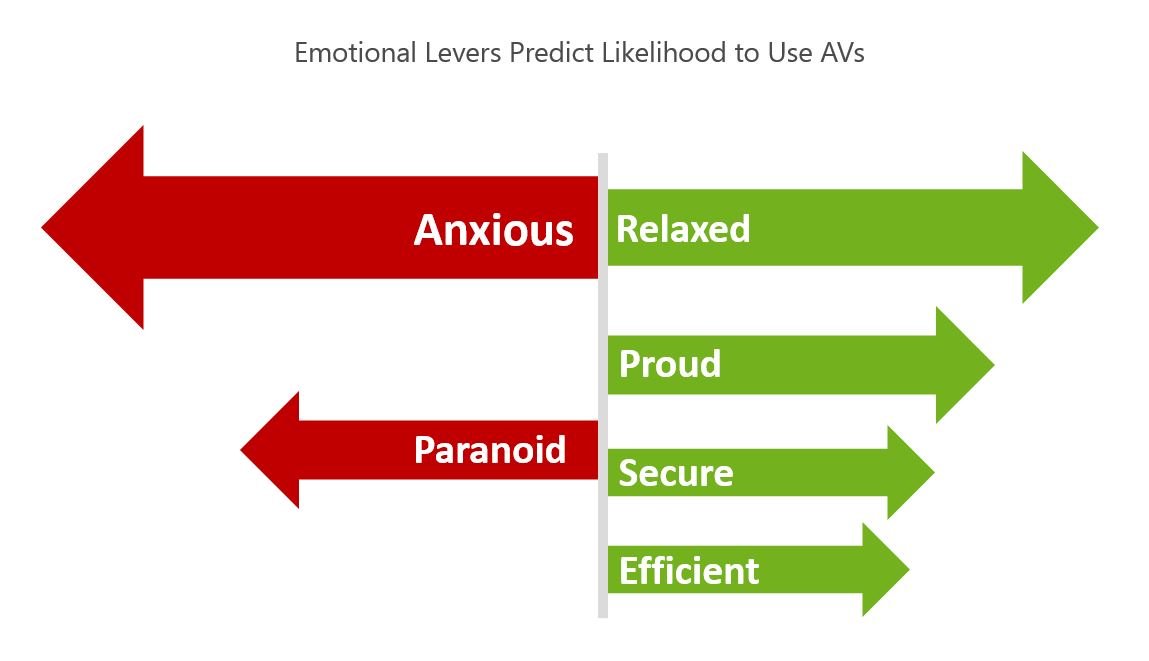

In addition to a straight gap analysis, we also ran a model to isolate which specific emotions (negative and positive) best predict (on a derived basis) peoples’ willingness to use autonomous vehicles in the future.

By far the biggest predictors, not surprisingly, are reducing anxiety and increasing feelings of relaxation.

Another emotion that popped in our predictive modelling, which wasn’t evident from the initial data review, was activating emotions around pride. In other words, people who would feel “proud” using an autonomous vehicle are much more likely to actually use one, whereas people who might feel ashamed or embarrassed if their friends or family saw them inside an autonomous vehicle are highly unlikely to hop on board.

This “social identity” element is something we see in many new tech adoption studies through our proprietary consumer-centric approach to measuring the impact of identity on decision-making. Does someone identify as being one of those people who uses an autonomous vehicle, or is that for another tribe altogether? Turns out this tribal identity matters quite a bit for new technologies attempting to cross the chasm.

Feeling “Secure” and “Efficient” also help predict likelihood to adopt the technology, but as we saw earlier, not many people feel these emotions when they think about using an autonomous vehicle.

In my next article, I will share some thoughts and findings from this study on potential paths forward for the industry to overcome these obstacles. You’ll get to see the results when I attempt to play an Ad Man and convince people to reconsider the category. Although it was a humbling experiment, it did reveal additional insights that can help actual creative teams with briefs that include different value propositions linked to specific emotions the industry needs to address.